It’s one of those questions that seems to come up in casual conversation among friends: ‘Why don’t they put a giant parachute on planes in case something happens?’ The answer, as so often, has to do with size, weight and aerodynamics. But there is one detail that is often overlooked: that idea is no longer just a question.

In a corner of the United States, an aircraft manufacturer decided to give it a try. And they succeeded. Today, their planes are equipped as standard with a system capable of deploying a ballistic parachute that can save the lives of all occupants. The company that achieved this is called Cirrus Aircraft, and it has been designing light aircraft for general aviation for decades.

Its proposal was as simple as it was revolutionary: incorporate a ballistic parachute directly into the fuselage as part of the aircraft’s design. Not as an accessory, not as an option. As standard. The system is called CAPS, which stands for Cirrus Airframe Parachute System, and is featured in both the SR series and the Vision Jet, a turbofan-powered aircraft for five passengers plus the pilot.

A parachute that is not an accessory, but part of the aircraft

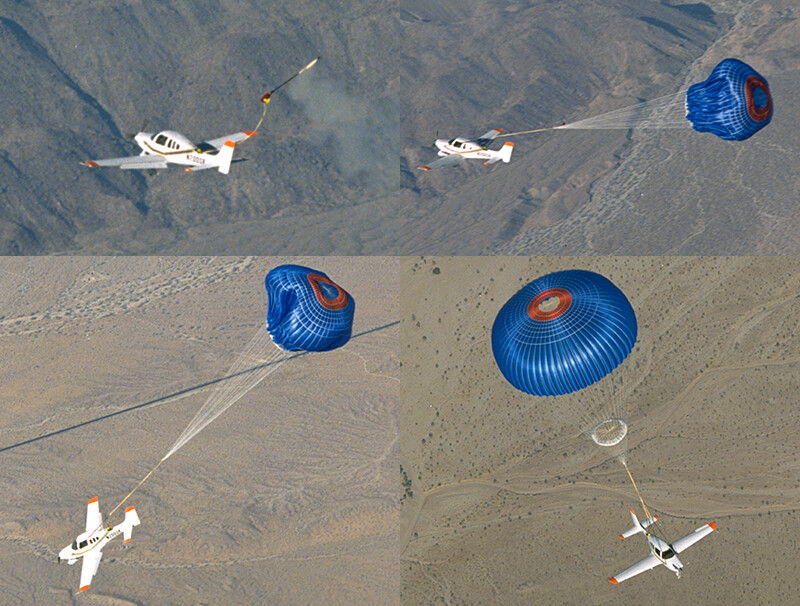

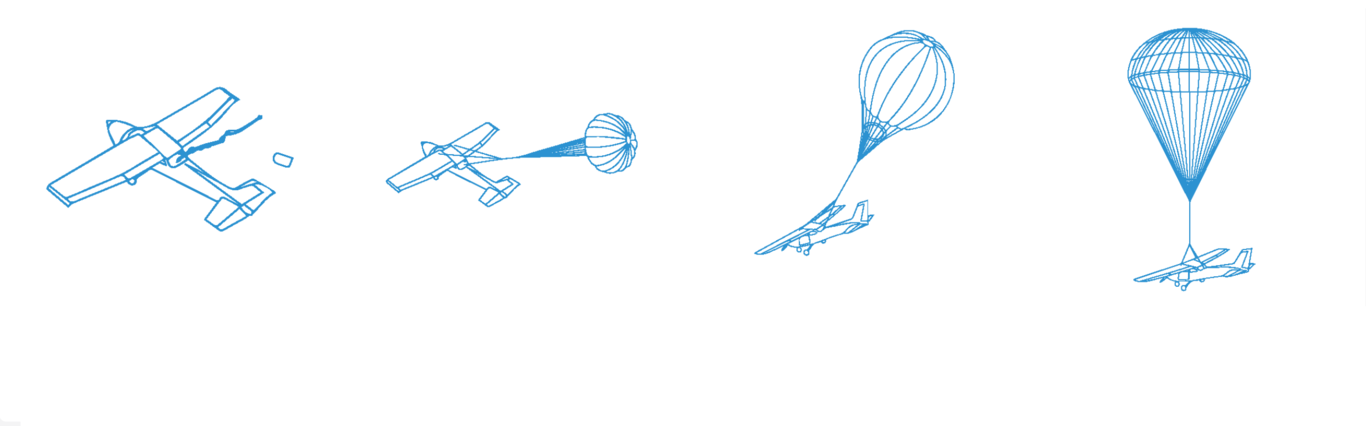

The CAPS works as simply as its objective: to save lives when all else fails. Hidden in the upper part of the fuselage, just behind the cockpit, is a sealed capsule containing a large parachute. In the event of a serious emergency, the pilot simply has to pull a T-shaped lever located on the cockpit ceiling. In a matter of seconds, a small rocket propels the parachute upwards and it deploys, slowing the aircraft’s descent until it touches the ground.

However, there are conditions. The system should not be activated below 600 feet (about 180 metres above ground level), and it is much more effective if deployed between 600 and 2,000 feet. Above that altitude, the pilot has more leeway to assess and make decisions, but it remains a valid option if the situation demands it.

The history of CAPS was not built overnight. In the mid-1990s, Cirrus’ engineering team, led by Paul Johnston, began working on an idea that, at the time, seemed crazy: adapting a complete parachute system to a light aircraft. They were inspired by an earlier prototype developed by BRS (Ballistic Recovery Systems), a company specialising in ballistic parachutes, which had already tested similar solutions for aircraft such as the Cessna 150.

In 1998, Cirrus conducted its first real-world test in the Southern California desert. A military pilot was responsible for activating the system. That test was crucial: it proved that the concept worked. From there, Cirrus integrated it as a central part of the design of its first major production model, the SR20. Not as an add-on, but as a structural element designed from the ground up.

Since its certification, the CAPS system has been activated more than a hundred times in emergency situations. According to COPA data, as of June 2025, there had been 136 deployments. Among them are stories of people who survived engine failure, loss of control, and extreme weather conditions.

On its official website, Cirrus claims that its system has brought more than 250 people home alive. And some of those stories are particularly striking. Like that of Greg Huntley, a pilot and owner of a Cirrus aircraft, who suffered an engine failure on 22 October 2014.

He activated CAPS and managed to land with the plane hanging from the parachute. He was unharmed. Huntley flew every week for work. He was based in Charlotte, North Carolina, and although he was never passionate about aviation, he recognised that it saved him a lot of time. On 22 October 2014, he took off like any other day. A few minutes into the flight, at an altitude of about 5,000 feet, the engine stopped dead.

‘Just before declaring an emergency, I thought: I have five minutes to live,’ he would later recall.

He made a clear decision: if he still couldn’t see the ground at 3,000 feet, he would activate the parachute. And so he did. The sky was still completely black through the windscreen, so he radioed that he was going to deploy the CAPS. ‘I’ve taken many children and their parents on their first flights. I always explain to them that if anything happens to me, they should pull the lever (…) That morning, as I put my hands on the handle, I thought: now it’s up to you to find out.’ The plane descended and in less than a minute touched down on a grass field.

The culmination of this philosophy came with the Cirrus Vision Jet, a small single-engine jet certified in 2016. It was the world’s first jet equipped as standard with a ballistic parachute for the entire aircraft. But Cirrus went even further: the CAPS system was supplemented by Safe Return, a feature that allows the aircraft to land on its own in an emergency.

The idea is simple. If the pilot suddenly becomes incapacitated, any passenger can press a button. At that moment, the Vision Jet takes over everything: it calculates the route, communicates the situation to air traffic controllers and autonomously descends to a safe runway. CAPS and Safe Return thus form a fairly comprehensive safety package.

The Cirrus parachute system is not designed for all types of aircraft. Nor is it intended to be. Its effectiveness depends on the type of aircraft in which it is integrated, its weight, its structure and the situations for which it was designed. While it is not perfect, it has opened a door: it has shown that there is room to think about safety from a different angle.