The human body begins to change almost immediately after death. Soft tissues, in particular, degrade rapidly due to the combined action of bacteria, enzymes and microorganisms that inhabit the body itself. Heat, humidity, or exposure to the open air can accelerate the process, while extreme cold or the absence of oxygen tend to slow it down dramatically. Under normal conditions, the decomposition of the brain begins within a few hours, leaving hardly any recognisable traces. However, a discovery in Turkey has defied all expectations.

An archaeological discovery breaks everything we knew about human decomposition

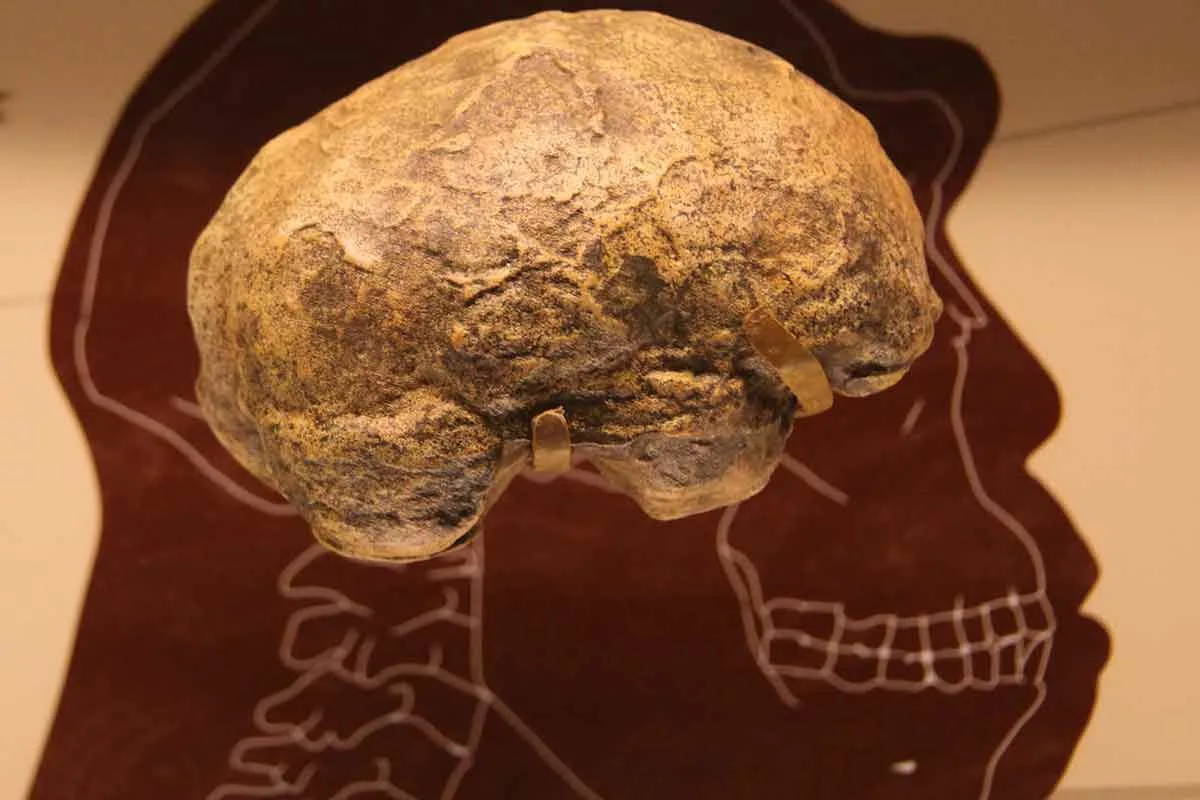

An archaeological team located one of the best-preserved human brains from the Bronze Age at the Seyitömer Höyük site. The find, recorded in the western region of the country, revealed that the brain tissue belonged to an individual who died about 4,000 years ago. Although the preservation of soft organs in such ancient contexts is very rare, researchers were able to analyse the structure of the brain with a level of detail that is difficult to imagine in remains from that period.

The state of preservation, according to subsequent analysis led by scientists at the University of Zurich, made it possible to identify the frontotemporal parts of the brain. This opened the door to investigating the health of prehistoric inhabitants, from possible haemorrhages to signs of degenerative diseases. Frank Rühli, a specialist in historical anatomy, stated in the study published by HOMO – Journal of Comparative Human Biology in 2014 that ‘the level of preservation in combination with the age is extraordinary’.

Unlike other cases, such as that of a naturally mummified Inca girl in the Andes, the preservation of the Turkish brain was not the result of the cold. Evidence points to a violent sequence of natural phenomena. The research team, led by Meriç Altınoz from Haliç University, concluded that the person had died during an earthquake that destroyed their settlement. The ruins were quickly buried, and shortly afterwards a fire spread through the rubble.

The environmental conditions were as extreme as they were favourable for preserving the tissue

The combination of extreme heat, lack of oxygen and subsequent drop in humidity was decisive. The brain matter cooked inside the skull, sealed by the remains of the collapse. Over time, this unventilated environment prevented the usual decomposition. Added to this was the composition of the soil, rich in aluminium, potassium and magnesium. This mineral mixture favoured the appearance of adipocere, a waxy substance that helps to maintain the shape of soft tissues for centuries.

Biochemical and sedimentological analyses provided insight into the unique conditions of the environment. Altınoz and his team identified charred wood remains next to the skeletons, confirming the presence of the fire. This layer of ash reinforced the isolation of the environment and helped preserve the brain in a surprising condition.

Until now, few archaeologists had considered the possibility of finding brain remains in such ancient excavations. Most assumed that decomposition would make preservation impossible. However, this case could mark a change in approach. In the same article, the Swiss team emphasised that ‘if cases like this are published, more and more people will become aware that original brain tissue can also be found.’

Beyond the exceptional value of the find, the scientists pointed out that having well-preserved brain tissue opens up new avenues of study into the neurological health of the past. Although the context was extreme, its analysis still offers a direct window into the living conditions, death and diseases that affected prehistoric populations.