A team of Italian scientists has drawn up a plan to reach one of the most distant and enigmatic objects in our solar system: the dwarf planet Sedna.

Two options. The research, pre-published on arXiv, details two spacecraft concepts to drastically shorten the journey to Sedna. Not only with the aim of doing it in less time, but also fast enough to arrive before the dwarf planet plunges back into the darkness of deep space for thousands of years.

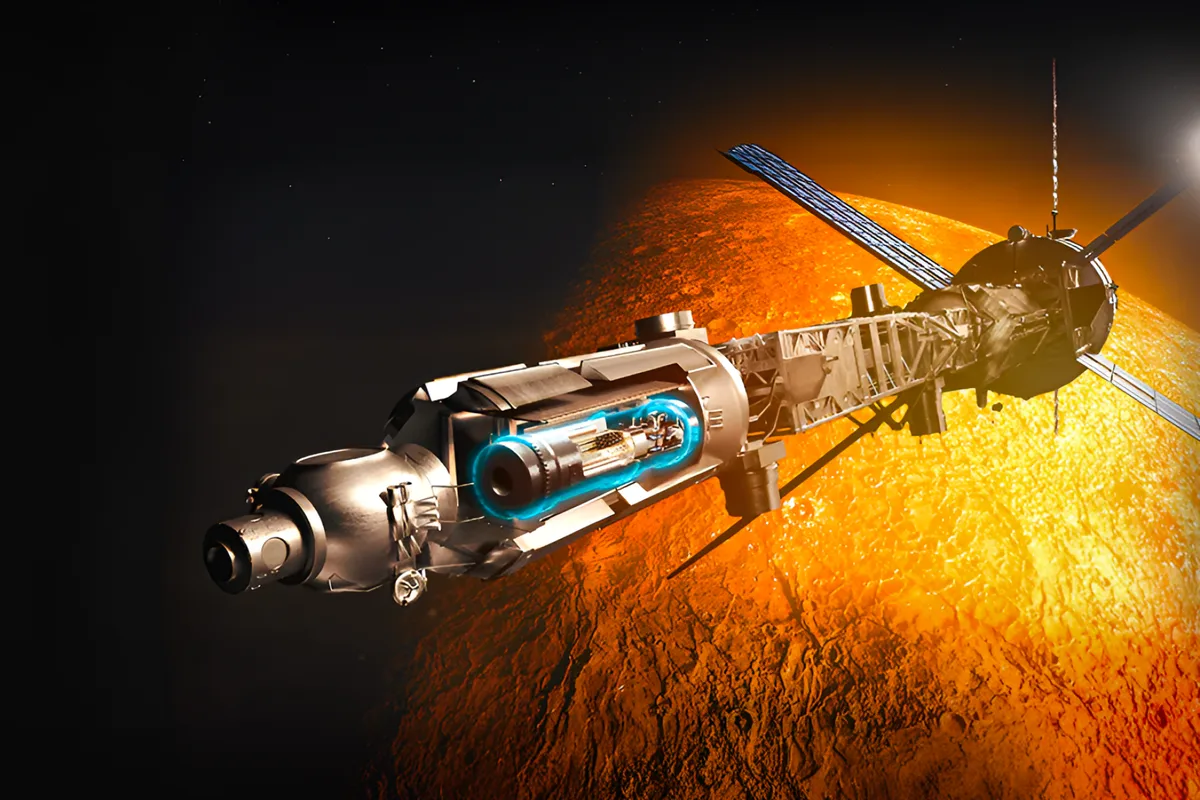

One is a high-tech solar sail that, according to the researchers, could make the journey in just seven years. The other is a nuclear fusion rocket that would take about ten years, but with a major advantage: it could enter orbit once there.

Timing is key. The planet Sedna, discovered in 2003, has an extremely eccentric orbit that lasts about 11,000 years. In 2076, it will reach its perihelion, the point in its orbit closest to the Sun, although ‘close’ is a relative term: it will be almost 11 billion kilometres away, two and a half times the distance from Neptune to our star.

It is a once-in-a-millennium opportunity to send a probe. With current rocket technology, such a journey would take between 20 and 30 years, requiring the development of an incredibly complex and high-budget mission in record time.

The cheap alternative. The first option is a solar sail that harnesses the thrust of the Sun’s photons to propel the spacecraft, a concept already tested in missions such as LightSail 2 by the Planetary Society. However, this sail would go one step further: it would be coated with a material that, when heated by sunlight, would release molecules through a process of thermal desorption, providing additional thrust.

Thanks to Jupiter’s gravitational assistance, this ultra-light spacecraft could reach Sedna in just seven years. The big advantage is that it would not need to carry the weight of fuel. The disadvantage is that it would carry a tiny payload (1.5 kg) and could only perform a flyby, passing quickly by Sedna, as the New Horizons probe did with Pluto. It would collect valuable data, but not much.

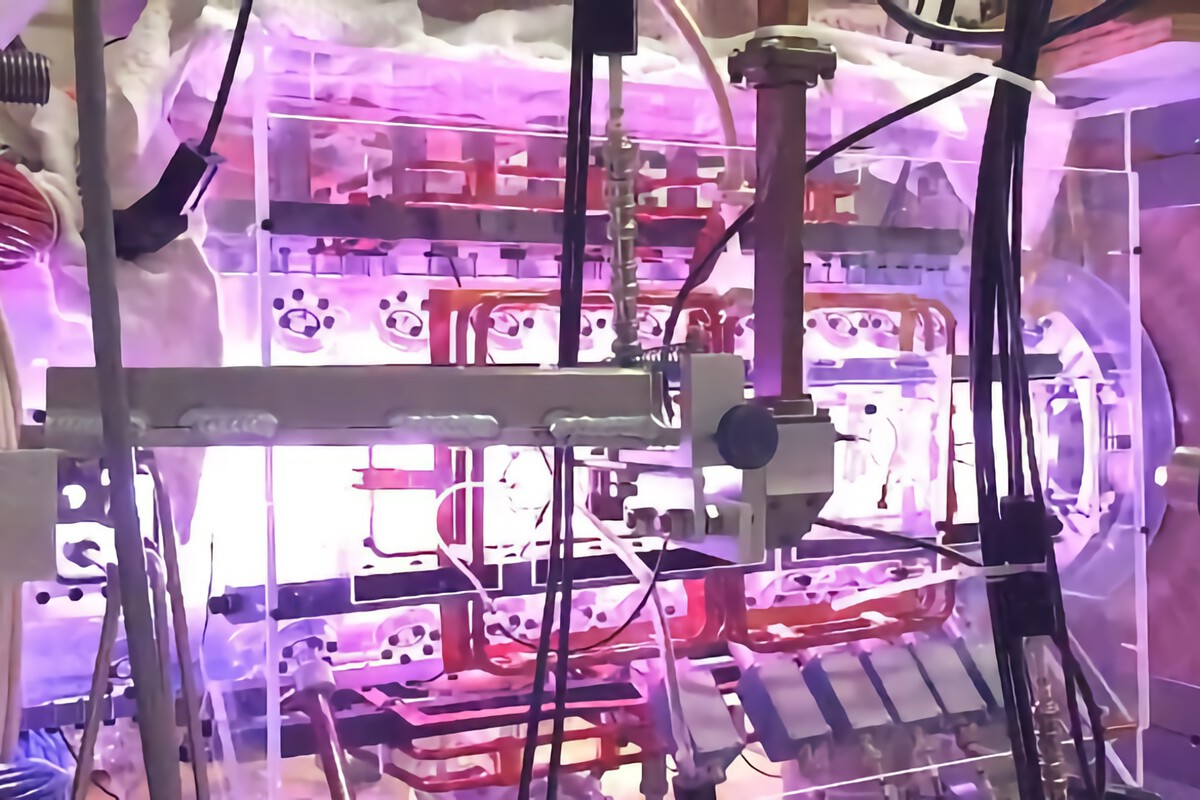

The ambitious alternative. The second proposal is more ambitious: a rocket powered by the direct fusion engine already under development at Princeton University’s Plasma Physics Laboratory. This engine would not only generate thrust, but also electrical energy from a controlled nuclear fusion reaction, providing continuous and powerful acceleration.

A trip with the nuclear engine would take ten years. Although slower than the solar sail, it has a greater reward: the ability to insert the spacecraft into Sedna’s orbit, making a much more detailed long-term study of its surface, composition and interaction with the space environment possible compared to the solar sail. The spacecraft itself could carry up to 1,500 kg of instruments.

Why Sedna? Not just because it is a trans-Neptunian object, an icy body orbiting beyond Neptune. Its reddish surface and extreme orbit make it a pristine relic of the formation of the solar system. Scientists believe that Sedna could contain organic compounds and water ice, the original ‘building blocks’ of planets.

Since it spends most of its time far from the Sun, its surface has been protected from radiation and heat, remaining almost untouched. One of the most fascinating hypotheses is that Sedna could be an exoplanet captured by our solar system during a stellar encounter in the past. Being able to analyse its composition in situ would literally be like studying material from another star system without leaving our own.